Lessico

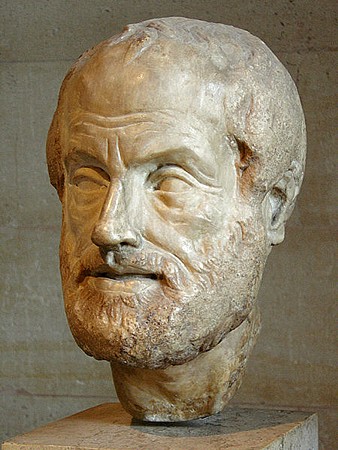

Aristotele

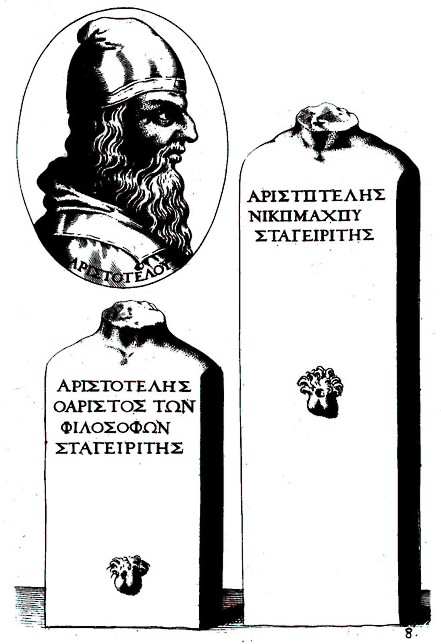

Icones veterum aliquot ac recentium Medicorum

Philosophorumque

Ioannes Sambucus / János Zsámboky![]()

Antverpiae 1574

Filosofo

greco (Stagira![]() 384 - Calcide 322 aC). Nacque

appunto a Stagira, piccola città ionica

presso la costa orientale della penisola calcidica, figlio di Nicomaco, medico

personale di Aminta II di Macedonia. Rimasto orfano in minore età, venne

adottato da un parente, Prosseno di Atarneo e si trasferì in questa città.

384 - Calcide 322 aC). Nacque

appunto a Stagira, piccola città ionica

presso la costa orientale della penisola calcidica, figlio di Nicomaco, medico

personale di Aminta II di Macedonia. Rimasto orfano in minore età, venne

adottato da un parente, Prosseno di Atarneo e si trasferì in questa città.

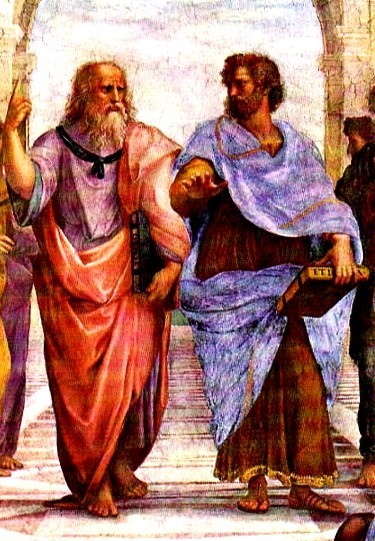

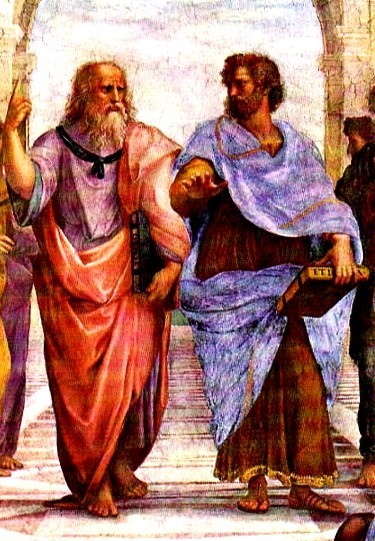

Aristotele con Platone alla sua destra - Raffaello Scuola di Atene

La Scuola di Atene (1509-10) fa parte del ciclo di affreschi dipinti da Raffaello per la Stanza della Segnatura nei Palazzi Vaticani. L'opera, che raffigura Aristotele e Platone insieme ad altri filosofi dell'antichità, appartiene al periodo della maturità artistica del pittore. La grandiosa concezione e il possente impianto prospettico, uniti allo straordinario fascino della rievocazione di uno fra i momenti più alti nella storia della civiltà occidentale, fanno di questo affresco uno dei più celebri capolavori del Rinascimento.

A diciotto

anni giunse ad Atene, alla scuola di Platone![]() ,

e vi rimase fino alla morte del maestro (347 aC). Andò poi ad Asso, nella

Troade, alla corte del tiranno Ermia, dove esisteva una comunità

filosofico-politica di tipo platonico, e qui probabilmente conobbe Teofrasto

,

e vi rimase fino alla morte del maestro (347 aC). Andò poi ad Asso, nella

Troade, alla corte del tiranno Ermia, dove esisteva una comunità

filosofico-politica di tipo platonico, e qui probabilmente conobbe Teofrasto![]() ,

col quale si recò nel 345-344 a Mitilene sull’isola di Lesbo.

,

col quale si recò nel 345-344 a Mitilene sull’isola di Lesbo.

Nel 343 fu

chiamato da Filippo II re di Macedonia![]() alla corte di Pella come precettore del figlio Alessandro

alla corte di Pella come precettore del figlio Alessandro![]() (là dove

quarant'anni prima aveva lavorato suo padre Nicomaco): a Mieza, presso Pella,

egli seppe inculcare ad Alessandro l'ideale della superiorità della cultura

ellenica e della sua universale capacità di espansione e dominio.

(là dove

quarant'anni prima aveva lavorato suo padre Nicomaco): a Mieza, presso Pella,

egli seppe inculcare ad Alessandro l'ideale della superiorità della cultura

ellenica e della sua universale capacità di espansione e dominio.

Nel 335 tornò ad Atene, dove ormai era prevalso il partito filomacedone, e vi fondò una scuola, il Liceo, così chiamata perché aveva la sua sede fra i viali intorno al tempio di Apollo Liceo; poiché gli insegnamenti più ristretti venivano tenuti passeggiando per questi viali i filosofi aristotelici vennero anche chiamati peripatetici. Qui insegnò per tredici anni, fino alla morte di Alessandro (323).

Accusato d'empietà dal partito antimacedone, fuggì a Calcide, nell’Eubea, dove si trovava una proprietà della madre, e dove morì l'anno dopo di malattia.

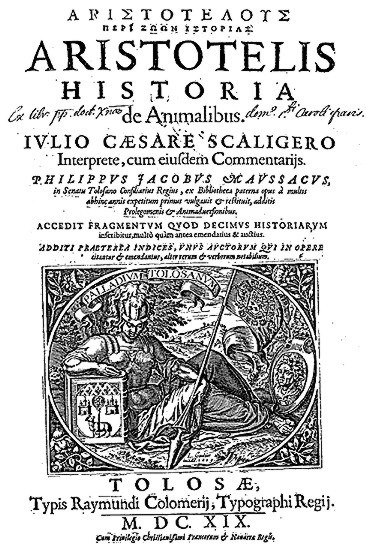

Citiamo almeno le sue opere biologiche, che sono le seguenti: Historia animalium, de Partibus animalium, de Incessu animalium, de Generatione animalium, de Motu animalium, Parva naturalia. I Parva naturalia comprendono: de Divinatione per somnum, de Insomniis, de Longitudine et brevitate vitae, de Memoria et reminiscentia, de Respiratione, de Sensu et sensilibus, de Somno et vigilia.

Grillo o Sulla retorica

Intorno al

360 aC il giovane Aristotele scrive la sua prima opera intitolata Grillo

o Sulla retorica; in reazione a una serie di scritti di elogio -

composti da alcuni retori ateniesi, fra i quali Isocrate![]() , per celebrare

Grillo, figlio di Senofonte

, per celebrare

Grillo, figlio di Senofonte![]() , morto nel 362 aC nella battaglia di Mantinea -

lo Stagirita polemizzava contro la retorica come mezzo per agire sugli

affetti, sulla parte irrazionale dell'anima. Già Platone

, morto nel 362 aC nella battaglia di Mantinea -

lo Stagirita polemizzava contro la retorica come mezzo per agire sugli

affetti, sulla parte irrazionale dell'anima. Già Platone![]() , nel Gorgia,

aveva sostenuto che la retorica non era un'arte, né una scienza, ma

semplicemente una pratica persuasiva che può avere successo solo sugli

ignoranti. Il successo del Grillo nell'Accademia procurò ad Aristotele

l'incarico di tenere un corso di retorica, nel quale, seguendo il Fedro

platonico, sostenne che la retorica doveva fondarsi sulla dialettica.

, nel Gorgia,

aveva sostenuto che la retorica non era un'arte, né una scienza, ma

semplicemente una pratica persuasiva che può avere successo solo sugli

ignoranti. Il successo del Grillo nell'Accademia procurò ad Aristotele

l'incarico di tenere un corso di retorica, nel quale, seguendo il Fedro

platonico, sostenne che la retorica doveva fondarsi sulla dialettica.

Sulle idee

Scritto poco dopo il Grillo, il trattato Sulle idee è andato

perduto e pochi frammenti sono stati trasmessi da Alessandro d'Afrodisia![]() . Vi

si affrontava la difficoltà di intendere il rapporto tra idee e cose,

concepito da Platone come partecipazione delle cose alle idee che da esse sono

tuttavia separate.

. Vi

si affrontava la difficoltà di intendere il rapporto tra idee e cose,

concepito da Platone come partecipazione delle cose alle idee che da esse sono

tuttavia separate.

Eudosso sosteneva che tra le idee e le cose non ci fosse né separazione, né partecipazione ma míxis, mescolanza: le idee e le cose sono mescolate tra loro. Aristotele non accetta la teoria eudossiana, che non risolve il problema, ma critica anche la teoria platonica della separazione, delle cui aporie lo stesso Platone era del resto ben consapevole, come mostra il suo dialogo Parmenide. Per Aristotele le idee non sono trascendenti ma sono immanenti, ossia sono cause formali delle cose.

Sul bene

Platone e Aristotele

particolare della formella del Campanile di Giotto 1437-1439 - Firenze

di

Luca della Robbia (Firenze ca. 1400-1482)

Nel tentativo di superare un'altra difficoltà contenuta nella teoria delle idee le quali, essendo molteplici, hanno bisogno, secondo Platone, di essere giustificate da un principio unitario, Platone introdusse i principi dell'Uno (identificato con il Bene) e della Diade (il grande e il piccolo); il primo ha la funzione di principio formale e il secondo ha la funzione di principio materiale. L'Uno e la Diade, insieme, sono la causa delle idee-numeri e delle idee, mentre queste ultime sono la causa delle cose.

È probabile che le conclusioni del trattato aristotelico Sul bene, scritto intorno al 358 aC e del quale rimangono pochi frammenti, fossero quelle esposte nella matura Metafisica (A 6, 987 b 6 e segg.): «Platone chiamò idee gli esseri diversi da quelli sensibili e disse che di tutte le cose sensibili si parla in dipendenza dalle idee e secondo le idee: infatti le cose molteplici che hanno lo stesso nome delle idee esistono per partecipazione [...] ma che cosa fosse la partecipazione o l'imitazione delle idee è un problema che [Platone e i pitagorici] lasciarono aperto. Inoltre Platone dice che, oltre alle cose sensibili e alle idee, esistono le cose matematiche, che sono intermedie, e differiscono dalle cose sensibili perché sono eterne e immobili, e differiscono dalle idee per il fatto che ce ne sono molte simili tra loro, mentre ciascuna idea è unica in sé [...] Come principi, Platone poneva la Diade, cioè il grande e il piccolo, come materia, e poneva l'Uno come sostanza; dal grande e dal piccolo, per partecipazione all'Uno, si costituiscono le idee, che sono i numeri che nascono da quei principi [...] Platone sosteneva una tesi vicina a quella dei Pitagorici, e si poneva sulle loro posizioni, quando diceva che i numeri sono la causa della sostanza delle altre cose [...] egli ricorre soltanto a due cause, l'essenza e la causa materiale, perché le idee sono la causa dell'essenza delle altre cose, mentre l'Uno è causa dell'essenza delle idee».

Aristotele respinse dunque, già nel primo periodo della sua formazione, la teoria delle idee nella lunga elaborazione fatta da Platone ma, dalla meditazione su di essa, ne trasse la personale dottrina della causa formale e della causa materiale.

Eudemo o Sull'anima

Nel 354 aC, alla morte in guerra, presso Siracusa, dell'amico e compagno di

studi Eudemo![]() di Cipro, Aristotele scrisse, in forma consolatoria e non

speculativa, un altro dialogo, pervenuto in frammenti, l'Eudemo o Sull'anima,

nel quale, prendendo a modello il Fedone platonico, sosterrebbe la tesi

dell'immortalità dell'anima razionale, come indicato nella forma pur

problematica della posteriore Metafisica (? 3, 1070 a 24-26): «Se rimanga

qualche cosa dopo l'individuo, è una questione ancora da esaminare. In alcuni

casi, nulla impedisce che qualcosa rimanga: per esempio, l'anima può essere

una cosa di questo genere, non tutta, ma solo la parte intellettuale; perché

è forse impossibile che tutta l'anima sussista anche dopo».

di Cipro, Aristotele scrisse, in forma consolatoria e non

speculativa, un altro dialogo, pervenuto in frammenti, l'Eudemo o Sull'anima,

nel quale, prendendo a modello il Fedone platonico, sosterrebbe la tesi

dell'immortalità dell'anima razionale, come indicato nella forma pur

problematica della posteriore Metafisica (? 3, 1070 a 24-26): «Se rimanga

qualche cosa dopo l'individuo, è una questione ancora da esaminare. In alcuni

casi, nulla impedisce che qualcosa rimanga: per esempio, l'anima può essere

una cosa di questo genere, non tutta, ma solo la parte intellettuale; perché

è forse impossibile che tutta l'anima sussista anche dopo».

Per l'Aristotele maturo, l'anima non è un'idea ma una sostanza informante il corpo: nell'Eudemo è invece netta è l'opposizione fra anima e corpo sicché lo Jaeger la considerava dimostrazione dell'adesione completa del giovane Aristotele al platonismo; i sostenitori della precoce presa di distanza dello Stagirita da Platone intendono invece questa dichiarata opposizione come dipendente dall'intento consolatorio del dialogo, nel quale Aristotele avrebbe volutamente accentuato il destino ultraterreno dell'anima. In ogni caso, i frammenti dell'Eudemo non permettono di dedurre un'adesione alle dottrine platoniche delle idee separate dagli oggetti sensibili e della conoscenza fondata sulla reminiscenza.

Protreptico

Del Protreptico o Esortazione alla filosofia, conosciuto dalle

numerose citazioni contenute nell'opera di eguale titolo di Giamblico![]() ,

dedicato a Temisone, re di una città di Cipro, dovette essere scritto intorno

al 350 aC. Il Protreptico è un'esortazione alla filosofia, essendo

questa il più grande dei beni, dal momento che ha per scopo se stessa, mentre

le altre scienze hanno per fine qualcosa di diverso da sé. Aristotele

individua nell'essere umano la divisione fra anima e corpo: «una parte di noi

è l'anima e una parte è il corpo, l'una comanda e l'altra è comandata,

l'una si serve dell'altra e l'altra sottostà come uno strumento [...]

Nell'anima ciò che comanda e giudica per noi è la ragione, mentre il resto

ubbidisce e per natura è comandato [...] dunque l'anima è migliore del

corpo, essendo più adatta al comando, e nell'anima è migliore quella parte

che possiede la ragione e il pensiero», una divisione non vista come

opposizione, come nell' Eudemo, ma come collaborazione: il corpo è lo

strumento dell'agire dell'anima, anzi della parte razionale dell'anima.

,

dedicato a Temisone, re di una città di Cipro, dovette essere scritto intorno

al 350 aC. Il Protreptico è un'esortazione alla filosofia, essendo

questa il più grande dei beni, dal momento che ha per scopo se stessa, mentre

le altre scienze hanno per fine qualcosa di diverso da sé. Aristotele

individua nell'essere umano la divisione fra anima e corpo: «una parte di noi

è l'anima e una parte è il corpo, l'una comanda e l'altra è comandata,

l'una si serve dell'altra e l'altra sottostà come uno strumento [...]

Nell'anima ciò che comanda e giudica per noi è la ragione, mentre il resto

ubbidisce e per natura è comandato [...] dunque l'anima è migliore del

corpo, essendo più adatta al comando, e nell'anima è migliore quella parte

che possiede la ragione e il pensiero», una divisione non vista come

opposizione, come nell' Eudemo, ma come collaborazione: il corpo è lo

strumento dell'agire dell'anima, anzi della parte razionale dell'anima.

«Delle cose che sono generate, alcune sono generate dall'intelligenza e dall'arte, per esempio, la casa e la nave; altre sono generate non per arte ma per natura: degli esseri viventi e delle piante, infatti, la causa è la natura e per natura sono generate tutte le cose di tal specie; altre però sono generate anche per caso, e sono tutte quelle non generate né per arte, né per natura, né da necessità, e tutte queste cose, molto numerose, noi diciamo che sono generate per caso». Non vi è finalità nel caso ma vi è nell'arte e nella natura: la natura è l'ordine tendente a un fine, e il fine dell'uomo è la conoscenza. La filosofia è sia buona che utile, ma la bontà va privilegiata rispetto all'utilità: «alcune cose, senza le quali è impossibile vivere, le amiamo in vista di qualcosa di diverso da esse: e queste bisogna chiamarle necessarie e cause concomitanti; altre invece le amiamo per se stesse, anche se non ne consegua nulla di diverso, e queste dobbiamo chiamarle propriamente beni [...] Sarebbe quindi del tutto ridicolo cercare di ogni cosa un'utilità diversa dalla cosa stessa, e domandare: "Che cosa ci è giovevole? Che cosa ci è utile?". Colui che ponesse queste domande non assomiglierebbe in nulla a uno che conosce ciò che è bello e buono né a uno che sappia riconoscere che cosa è causa e che cosa è concomitante». È una polemica, questa, contro le posizioni di Isocrate che, nel suo Antidosis, scritto contro l'Aristotele del Grillo, attaccava una conoscenza che fosse priva di utilità pratica. Del resto, che fare filosofia sia per Aristotele comunque necessario lo dimostra il fatto che «chi pensa sia necessario filosofare, deve filosofare e chi pensa che non si debba filosofare, deve filosofare per dimostrare che non si deve filosofare; dunque si deve filosofare in ogni caso o andarsene di qui, dando l'addio alla vita, poiché tutte le altre cose sembrano essere solo chiacchiere e vaniloquio».

De philosophia

Il De philosophia, pervenuto in frammenti, fu scritto intorno al 355 aC

e si divide in tre libri: nel primo Aristotele definisce filosofia la

conoscenza dei principi della realtà; nel secondo critica la dottrina

platonica delle idee e delle idee-numeri; nel terzo espone la sua teologia.

Ribadisce la non trascendenza delle idee e nega le idee-numero o numeri

ideali, introdotti dal tardo Platone: «se le idee sono un'altra specie di

numero, non matematico, non potremmo averne alcuna comprensione; chi, fra noi,

comprende un tipo di numero diverso?». È Cicerone![]() (De natura deorum,

1, 13) a citare, criticamente, il terzo libro del De philosophia:: «Aristotele

nel terzo libro della sua opera Della filosofia confonde molte cose

dissentendo dal suo maestro Platone. Ora infatti attribuisce tutta la divinità

a una mente, ora dice che il mondo stesso è dio, ora prepone al mondo un

altro essere e gli affida il compito di reggere e governare il moto del mondo

per mezzo di certe rivoluzioni e moti retrogradi, talora dice che dio è

l'etere, non comprendendo che il cielo è una parte di quel mondo che altrove

ha designato come potere divino».

(De natura deorum,

1, 13) a citare, criticamente, il terzo libro del De philosophia:: «Aristotele

nel terzo libro della sua opera Della filosofia confonde molte cose

dissentendo dal suo maestro Platone. Ora infatti attribuisce tutta la divinità

a una mente, ora dice che il mondo stesso è dio, ora prepone al mondo un

altro essere e gli affida il compito di reggere e governare il moto del mondo

per mezzo di certe rivoluzioni e moti retrogradi, talora dice che dio è

l'etere, non comprendendo che il cielo è una parte di quel mondo che altrove

ha designato come potere divino».

La dimostrazione della necessità e dell'immutabilità di Dio è fornita dalla testimonianza di Simplicio (De Coelo, 228): «dove c’è un meglio, c’è anche un ottimo: poiché, fra ciò che esiste, c’è una realtà superiore a un'altra, esisterà di conseguenza una realtà perfetta, che dovrà essere la potenza divina [...] e ne deduce la sua immutabilità». Puro pensiero e immutabile, Dio non può creare il mondo, che è anch’esso eterno, come riporta Cicerone (Tuscolane, 15, 42): «il mondo non ha mai avuto origine, poiché non vi è stato alcun inizio, per il sopravvenire di una nuova decisione, di un'opera così eccellente» e attesta anche la concezione della divinità degli astri: «Le stelle poi occupano la zona eterea. E poiché questa è la più sottile di tutte ed è sempre in movimento e sempre mantiene la sua forza vitale, è necessario che quell'essere vivente che vi nasca sia di prontissima sensibilità e di prontissimo movimento. Per la qual cosa, dal momento che sono gli astri a nascere nell'etere, è logico che in essi siano insite sensibilità e intelligenza. Dal che risulta che gli astri devono essere ritenuti nel numero delle divinità».

L'abbandono dell'Accademia

e la fondazione del Peripato

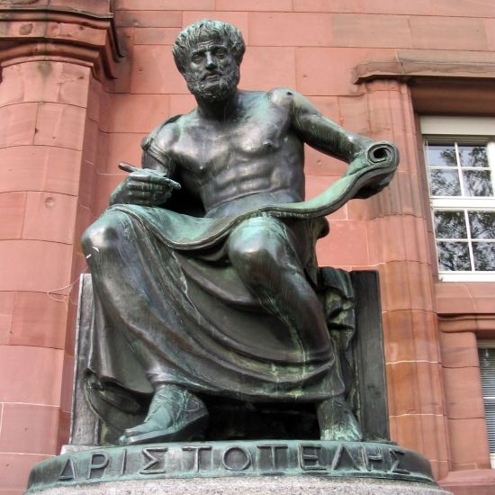

Statua di Aristotele a Calcide

Nel 347 aC muore Platone e alla direzione dell'Accademia viene chiamato

Speusippo, nipote del grande filosofo ateniese. Aristotele, che evidentemente

doveva ritenersi il più degno, lascia la scuola insieme con Senocrate, altro

pretendente alla guida dell'Accademia, per trasferirsi ad Atarneo, invitato

dal tiranno della città, Ermia, dove già operavano altri due allievi di

Platone, Erasto e Coristo. Nello stesso anno tutti e quattro si trasferiscono

ad Asso, dove fondano una scuola alla quale aderiscono anche il figlio di

Coristo, Neleo, e il futuro successore di Aristotele nella scuola di Atene,

Teofrasto![]() .

.

Nel 344 aC va a Mitilene, sull'isola di Lesbo, e v'insegna fino al 342, anno

in cui è chiamato in Macedonia dal re Filippo![]() perché faccia da precettore

al figlio Alessandro

perché faccia da precettore

al figlio Alessandro![]() . Da rilevare la continuità: Socrate è stato il maestro

di Platone, Platone di Aristotele, e Aristotele di Alessandro Magno. Quando

nel 340 aC Alessandro diviene reggente del regno di Macedonia, il suo maestro

Aristotele, che è intanto rimasto vedovo e convive con la giovane Erpilli da

cui ha avuto il figlio Nicomaco, torna forse a Stagira e, intorno al 335 aC,

si trasferisce ad Atene, dove in un pubblico ginnasio, detto Liceo perché

sacro ad Apollo Liceo, fonda una sua famosissima e celebrata scuola, chiamata

Peripato - passeggiata, dall'uso istituito dallo Stagirita di insegnare

passeggiando nel giardino che la circonda.

. Da rilevare la continuità: Socrate è stato il maestro

di Platone, Platone di Aristotele, e Aristotele di Alessandro Magno. Quando

nel 340 aC Alessandro diviene reggente del regno di Macedonia, il suo maestro

Aristotele, che è intanto rimasto vedovo e convive con la giovane Erpilli da

cui ha avuto il figlio Nicomaco, torna forse a Stagira e, intorno al 335 aC,

si trasferisce ad Atene, dove in un pubblico ginnasio, detto Liceo perché

sacro ad Apollo Liceo, fonda una sua famosissima e celebrata scuola, chiamata

Peripato - passeggiata, dall'uso istituito dallo Stagirita di insegnare

passeggiando nel giardino che la circonda.

Nel 323 aC muore Alessandro Magno e ad Atene si manifestano apertamente i mai sopiti odi antimacedoni; Aristotele, guardato con ostilità per il suo legame con la corte macedone, è accusato di empietà: lascia allora Atene e con la famiglia si rifugia a Calcide, la città materna, dove muore l'anno dopo.

Il testamento

Diogene Laerzio![]() (Vite V,11-16) riporta il testamento di Aristotele:

«Andrà senz'altro bene, ma qualora capitasse qualcosa, Aristotele ha steso

le seguenti disposizioni: tutore di tutti, sotto ogni aspetto, dev'essere

Antipatro; però, Aristomene, Timarco, Ipparco, Diotele e Teofrasto, se è

possibile, si prendano cura dei figli, di Erpillide [la sua convivente] e

delle cose da me lasciate, fino all'arrivo di Nicanore. E al momento giusto,

mia figlia [Piziade] sia data in sposa a Nicanore [...] Se invece Teofrasto

vorrà prendersi cura di mia figlia, allora sia padrone lui [...] I tutori e

Nicanore, ricordandosi di me, si prendano cura anche di Erpillide, sotto ogni

aspetto e anche se vorrà risposarsi, in modo che non sia data in sposa

indegnamente, visto che è stata premurosa con me. In particolare, le vengano

dati, oltre a quello che ha già ottenuto, anche un tallero d'argento e tre

schiave, quelle che vuole, la schiava che già ha e lo schiavo Pirro. E se

vorrà abitare a Calcide, le sia data la casa per gli ospiti vicino al

giardino; se invece vorrà stare a Stagira, le sia data la mia casa paterna

[...] Sia libera Ambracide e le si diano, alle nozze di mia figlia,

cinquecento dracme e la giovane serva che già possiede [...] Sia liberato

Ticone quando mi figlia si dovesse sposare, e così anche Filone, Olimpione e

il suo ragazzino. Non vendano nessuno dei giovani schiavi che attualmente mi

servono, ma siano impiegati; una volta dell'età giusta, siano liberati, se lo

meritano [...] Ovunque sia costruita la mia tomba, là siano portate e deposte

le ossa di Piziade, come lei stessa ordinò; dedichino poi anche da parte di

Nicanore, se sarà ancora vivo - come ho pregato a suo favore - statue di

pietra alte quattro cubiti a Zeus Salvatore e ad Atena Salvatrice a Stagira».

(Vite V,11-16) riporta il testamento di Aristotele:

«Andrà senz'altro bene, ma qualora capitasse qualcosa, Aristotele ha steso

le seguenti disposizioni: tutore di tutti, sotto ogni aspetto, dev'essere

Antipatro; però, Aristomene, Timarco, Ipparco, Diotele e Teofrasto, se è

possibile, si prendano cura dei figli, di Erpillide [la sua convivente] e

delle cose da me lasciate, fino all'arrivo di Nicanore. E al momento giusto,

mia figlia [Piziade] sia data in sposa a Nicanore [...] Se invece Teofrasto

vorrà prendersi cura di mia figlia, allora sia padrone lui [...] I tutori e

Nicanore, ricordandosi di me, si prendano cura anche di Erpillide, sotto ogni

aspetto e anche se vorrà risposarsi, in modo che non sia data in sposa

indegnamente, visto che è stata premurosa con me. In particolare, le vengano

dati, oltre a quello che ha già ottenuto, anche un tallero d'argento e tre

schiave, quelle che vuole, la schiava che già ha e lo schiavo Pirro. E se

vorrà abitare a Calcide, le sia data la casa per gli ospiti vicino al

giardino; se invece vorrà stare a Stagira, le sia data la mia casa paterna

[...] Sia libera Ambracide e le si diano, alle nozze di mia figlia,

cinquecento dracme e la giovane serva che già possiede [...] Sia liberato

Ticone quando mi figlia si dovesse sposare, e così anche Filone, Olimpione e

il suo ragazzino. Non vendano nessuno dei giovani schiavi che attualmente mi

servono, ma siano impiegati; una volta dell'età giusta, siano liberati, se lo

meritano [...] Ovunque sia costruita la mia tomba, là siano portate e deposte

le ossa di Piziade, come lei stessa ordinò; dedichino poi anche da parte di

Nicanore, se sarà ancora vivo - come ho pregato a suo favore - statue di

pietra alte quattro cubiti a Zeus Salvatore e ad Atena Salvatrice a Stagira».

Le opere

Della produzione filosofica aristotelica ci sono giunti solo gli scritti composti per il suo insegnamento nel Peripato, detti acroamatici o esoterici; ma Aristotele scrisse e pubblicò, durante la sua precedente permanenza nell'Accademia di Platone, anche dei dialoghi destinati al pubblico, per questo motivo detti essoterici, che sono però pervenuti in frammenti. Questi dialoghi giovanili furono letti e discussi dai commentatori fino al VI secolo dC.

Soprattutto a causa della soppressione dell'Accademia ateniese ordinata nel 529 da Giustiniano e alla diaspora di quegli accademici, tutti non cristiani, queste opere si dispersero e furono dimenticate, mentre di Aristotele rimasero solo i trattati esoterici; questi, a loro volta, erano stati dimenticati a lungo dopo la morte del Maestro e furono trovati, alla fine del II secolo aC da un bibliofilo ateniese, Apellicone di Teo, in una cantina appartenente agli eredi di Neleo, figlio di Corisco, entrambi seguaci di Aristotele nella scuola di Asso. Apellicone li acquistò, portandoli ad Atene e qui Silla li sequestrò nel saccheggio di Atene dell'84 aC, portandoli a Roma, dove furono ordinati e pubblicati da Andronico da Rodi. L'insieme di queste opere può essere ordinato per argomenti omogenei:

Logica, scritti raccolti nel titolo complessivo di Organon

- in greco,

"strumento" - comprendenti:

1 - Le categorie (un libro)

2 - De interpretatione (un libro)

3 - Analitici primi (due libri)

4 - Analitici secondi (due libri)

5 - Topici (otto libri)

6 - Elenchi sofistici (un libro)

Metafisica (quattordici libri)

Fisica (otto libri) con scritti correlati:

1 - Sul cielo (quattro libri)

2 - Sulla generazione e corruzione (due libri)

3 - Sulle meteore (quattro libri)

4 - Storia degli animali (un libro)

5 - Sulle parti degli animali (un libro)

6 - Sulla generazione degli animali (un libro)

7 - Sulle migrazioni degli animali (un libro)

8 - Sul movimento degli animali (un libro)

Sull'anima (tre libri) con scritti correlati:

1 - Sensazione e sensibile (un libro)

2 - Memoria e reminiscenza (un libro)

3 - Il sonno (un libro)

4 - I sogni (un libro)

5 - La divinazione mediante i sogni (un libro)

6 - Lunghezza e brevità della vita (un libro)

7 - Giovinezza e vecchiaia (un libro)

8 - La respirazione (un libro)

Etica, comprendente

1 - Etica Nicomachea (dieci libri)

2 - Etica Eudemia (sei libri)

3 - Grande etica (due libri)

Politica (otto libri) correlata alla

1 - Costituzione degli Ateniesi

Retorica (tre libri)

Poetica, incompiuta.

Ontologia

L'ontologia è la filosofia prima aristotelica che ha come oggetto l'ente. Aristotele intende per ente tutto ciò che è, tutto ciò che esiste: sarà perciò ente un uomo, così come sarà ente il suo colore di pelle. Ovviamente fra i due enti sussiste una notevole differenza, però entrambi devono essere ritenuti tali, per questo il filosofo afferma che ente è un "pollachos legomenon", ossia, si può "dire in molti modi".

Il filosofo distingue fra i vari enti 10 categorie entro cui classificarli sulla base della loro differenza: sostanza, qualità, quantità, dove, relazione, agire, patire, avere, giacere, quando. Le 10 categorie possono anche essere definite generi massimi, poiché permettono la completa classificazione degli enti. Non devono essere confuse con i 5 generi sommi platonici perché se il fondatore dell'Accademia cercò delle categorie cui partecipassero tutte le idee, Aristotele cerca delle categorie cui gli enti partecipino in base alla loro diversità, non esiste infatti nessuna categoria a cui tutti gli enti tangibili partecipino, proprio perché non era quello della reductio ad unum (l'omologazione, il confluire di tutti gli oggetto di studio in un unico grande calderone) il suo fine.

Il genere massimo di cui il filosofo si occupa di più è quello di sostanza, classificando sostanza prima e sostanza seconda. La prima è relativa ad un singolo essere, un determinato uomo o un certo animale, una pianta, e tutto ciò che ha sussistenza autonoma. La sostanza seconda, invece, è costituita da sostantivo generici che specificano meglio il "ti esti", "il che cos'è" la sostanza prima. Nella frase «il Sole è un astro» Sole, nome proprio e specifico di una stella, è sostanza prima, mentre astro, nome generico che ne specifica l'essenza, la natura, è sostanza seconda.

Relativamente alle altre categorie, esse si devono definire "accidenti" in quanto non hanno vita indipendente, se non nel momento in cui ineriscono alla sostanza. Il giallo, per esempio, non è un ente autonomo come un uomo. Perciò nella frase «il Sole è giallo», Sole è sempre sostanza prima, mentre giallo è accidente della sostanza, della categoria della qualità.

Lo stesso filosofo afferma che è inutile ogni scienza che si occupa di enti che riportano le stesse caratteristiche: la matematica studia gli enti astratti deducibili solo con l'astrazione( in numeri), la fisica gli elementi naturali della physis, l'ontologia, invece, studia gli enti. Ma in base a che cosa gli enti sono accomunati? Non certo il fatto di esistere, perché, come già detto, il filosofo nega a priori l'esistenza di una categoria che collochi in se tutti gli enti (la categoria dell'essere che, infatti, li accomunerebbe tutti). Il termine ente è, comunque, una parola equivoca, proprio come "salutare". Esso vuol dire sano o indicare l'azione del cordiale saluto, tutto comunque richiama allo stesso concetto di salute. "Ente" ha vari significato (è un "pollachos legomenon"), ma tutte le valenze che assume richiamano inevitabilmente in un modo o nell'altro il concetto di sostanza. Gli enti perciò, tutti, sono studiati dall'ontologia in quanto tutti ineriscono alla sostanza.

Dialettica

La dialettica, in Aristotele, è la tecnica con la quale uscire vittoriosi da una discussione. Questo successo deriva dal prevalere con la propria tesi su quella sostenuta dall'avversario, nel rispetto di premesse su cui ci si è messi d'accordo prima dell'inizio del confronto: difatti, la confutazione, l'aver ottenuto ragione e quindi l'aver vinto, si basava proprio sul portare l'interlocutore ad autocontraddirsi, mostrando dunque come la sua tesi, se sviluppata, avrebbe condotto a risultati illogici nei confronti delle premesse iniziali, considerate vere da entrambi. Certo era necessario che le premesse fossero considerate vere dal pubblico che assisteva al confronto, pertanto non di rado si sceglieva di accordarsi su premesse che fossero ritenute vere dai membri più influenti della società, così che essi potessero influenzare anche l'opinione altrui. La tecnica dialettica necessitava di un'ottima conoscenza delle parole e dei modi di unirle in proposizioni e, ancora, in periodi, pertanto il filosofo postula alcune teoria, quali quella della proposizione e quella del sillogismo, che permettono di capire come debba funzionare nei vari casi la parola. Prima di queste teorie, si sofferma sulla spiegazione dell'esistenza di parole univoche ed equivoche, ovvero da uno o più significato: deve essere la loro conoscenza accurata il primo necessario requisito per l'esperto di dialettica.

Teoria della proposizione

Una proposizione è un insieme di termini (parole) che danno vita a un'affermazione, un giudizio. Questo può essere verità o falso, in base al riscontro con la realtà, mentre i singoli termini non possono essere veri o falsi se considerati singolarmente; tuttavia non tutte le proposizioni sono vere o false: preghiere, invocazioni, ordini, sono destinate all'ambito poetico e di esse Aristotele non si occupa. Invece si occupa delle frase a cui sole può essere riconosciuta la possibilità di essere vere o false, chiamate categoriche, o dichiarative, o apofantiche. Le proposizioni categoriche possono avere qualità affermativa o negativa e quantità universale (quando il soggetto è un genere e vi sono inclusi tutti gli appartenenti), particolare (si fa riferimento solo a una parte degli enti di un genere) o singolari (il soggetto è un individuo singolo), in base alla maggiore o minore generalità del soggetto. Aristotele non si preoccupa delle proposizioni singolari, soffermandosi solo sulle proposizioni affermative e negative, universali e particolari. Combinando questi tipi di proposizioni, risultano esserci quattro tipi di proposizioni-modello per il filosofo, le quali sono universale affermativa, universale negativa, particolare affermativa e particolare negativa.

Il concetto di Philia

Aristotele tratta del concetto d'amicizia (in greco philia) nell'ottavo e nel nono libro dell'Etica Nicomachea. Il filosofo comincia facendo l'analisi dei diversi fondamenti dell'amicizia: l'utile, il piacere e il bene; da questi derivano le tre tipologie d'amicizia: quella di utilità, di piacere e di virtù. L'amicizia di utilità è tipica dei vecchi, quella di piacere degli uomini maturi e dei giovani; gli amici in queste due tipologie non si amano di per se stessi ma solamente per i vantaggi che traggono dal loro legame: per questo motivo questi tipi di amicizia, basandosi sui bisogni e desideri umani, che sono volubili, si dissolvono e si creano con facilità. L'unica vera amicizia è quella di virtù, stabile perché si fonda sul bene, caratteristica degli uomini buoni. L' amicizia di virtù presuppone due cose fondamentali: l'uguaglianza fra gli amici (intelligenza, ricchezza, educazione ecc.) e la consuetudine di vita. L'amicizia si distingue dalla benevolenza, che può non essere corrisposta e dall'amore, perché nell'amore entrano in gioco fattori istintuali. Tuttavia Aristotele non esclude che un rapporto d'amore possa trasformarsi poi in una vera e propria amicizia. La philia aristotelica esprime il legame tra amicizia e reciprocità, fondato sul riconoscimento dei meriti e sul desiderio reciproco del bene per l'altro.

Aristotele e l'astronomia

Aristotele tratta nelle sue opere (in particolare nella Fisica) della conformazione dell'universo. Aristotele propone un modello geocentrico, cioè che pone la Terra al centro dell'universo. Fatale errore che, per l'autorevolezza del maestro, durerà per 1800 anni, sino a Nicolò Copernico.

Secondo Aristotele, la Terra era formata da quattro elementi: la terra, l'aria, il fuoco e l'acqua. Le varie composizioni degli elementi costituivano tutto ciò che c'era sulla terra. Ogni elemento aveva due delle quattro caratteristiche (o "attributi") della materia: il secco (terra e fuoco), l'umido (aria ed acqua), il freddo (acqua e terra) e il caldo (fuoco e aria). Ogni elemento aveva la tendenza a rimanere o a tornare nel proprio luogo naturale, che per la terra e l'acqua è il basso, mentre per l'aria e il fuoco è l'alto. La Terra come pianeta, quindi, non può che stare al centro dell'universo, poiché è formata dai due elementi tendenti al basso, e il "basso assoluto" è proprio il centro dell'universo.

Per quanto riguarda ciò che esiste oltre la Terra, Aristotele lo riteneva fatto di un quinto elemento (o essenza): l'etere. L'etere, che non esiste sulla terra, sarebbe privo di massa, invisibile e, soprattutto, eterno e inalterabile: queste due ultime caratteristiche sanciscono un confine tra i luoghi del mutamento (la Terra) e i luoghi immutabili (il cosmo).

Aristotele credeva che i corpi celesti si muovessero su sfere (in numero di cinquantacinque, ventidue in più delle 33 di Callippo). Oltre la Terra c'erano, in ordine, la Luna, Mercurio, Venere, il Sole, Marte, Giove, Saturno, la sfera delle stelle fisse e, infine, il primo mobile, cioè il "motore", della cui natura peraltro Aristotele ebbe qualche difficoltà a dare una definizione precisa, che metteva tutte le altre sfere in movimento. Identificabile con la divinità suprema (le altre divinità stavano all'interno del cosmo), esso è la causa prima di tutti i moti celesti.

Aristotele era convinto dell'unicità e della finitezza dell'universo: l'unicità perché se esistesse un altro universo sarebbe composto sostanzialmente delle medesime essenze del nostro e quindi tenderebbe, per i luoghi naturali, ad avvicinarsi al nostro e perciò con esso si ricongiungerebbe, ciò che prova l'unicità del nostro universo; la finitezza perché in uno spazio infinito non potrebbe esserci un centro, ciò che contravverrebbe alla teoria dei luoghi naturali.

Biologia

Aristotele ha fondato la biologia come scienza empirica, compiendo un importante salto di qualità (almeno stando alle fonti che ci sono rimaste) nell'accuratezza e nella completezza descrittiva delle forme viventi, e soprattutto introducendo importanti schemi concettuali che si sono conservati nei secoli successivi.

L'Historia animalium contiene la descrizione di 581 specie diverse,

osservate per lo più durante la permanenza in Asia Minore e a Lesbo. Questi

dati biologici vengono organizzati e classificati nel De partibus animalium,

nel quale vengono introdotti concetti fondamentali come quello di viviparità

e oviparità, e sono impiegati criteri di classificazione delle specie in base

all'habitat o a precise caratteristiche anatomiche, che sono in gran parte

rimasti inalterati fino a Linneo![]() . Un'altrettanto importante conquista

intellettuale è lo studio sistematico di quella che oggi chiamiamo anatomia

comparata, che permette ad esempio ad Aristotele di classificare Delfini e

Balene tra i mammiferi (essendo essi dotati di polmoni e non di branchie come

i pesci).

. Un'altrettanto importante conquista

intellettuale è lo studio sistematico di quella che oggi chiamiamo anatomia

comparata, che permette ad esempio ad Aristotele di classificare Delfini e

Balene tra i mammiferi (essendo essi dotati di polmoni e non di branchie come

i pesci).

Il De generatione animalium si occupa del modo in cui gli animali si riproducono. In quest'opera la generazione viene interpretata come trasmissione della forma (di cui è portatore il seme maschile) alla materia (rappresentata dal sangue mestruale femminile). Secondo Aristotele le specie sono eterne ed immutabili, e la riproduzione non determina mai cambiamenti nella sostanza, ma solo negli accidenti dei nuovi individui. Molto interessante è lo studio che Aristotele compie sugli embrioni, grazie al quale egli comprende che essi non si sviluppano attraverso la crescita di organi già tutti presenti fin dal concepimento, ma con la progressiva aggiunta di nuove strutture vitali.

Alcuni limiti della biologia aristotelica (come la generale sottovalutazione del ruolo del cervello, che Aristotele credeva destinato a raffreddare il sangue) furono superati con la scoperta (avvenuta in epoca ellenistica) del sistema nervoso, ma in molti altri casi per arrivare a un superamento della biologia aristotelica si è dovuto attendere lo sviluppo scientifico del pieno Settecento.

Statua in ricordo di Aristotele - Università di Friburgo in Germania

Aristotle (Greek Ἀριστοτέλης Aristotélës) (384 BCE – 322 BCE) was a Greek philosopher, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. He wrote on many different subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, politics, government, ethics, biology and zoology.

Aristotle (together with Socrates and Plato) is one of the most important founding figures in Western philosophy. He was the first to create a comprehensive system of philosophy, encompassing morality and aesthetics, logic and science, politics and metaphysics. Aristotle's views on the physical sciences profoundly shaped medieval scholarship, and their influence extended well into the Renaissance, although they were ultimately replaced by modern physics. In the biological sciences, some of his observations were only confirmed to be accurate in the nineteenth century. His works contain the earliest known formal study of logic, which were incorporated in the late nineteenth century into modern formal logic. In metaphysics, Aristotelianism had a profound influence on philosophical and theological thinking in the Islamic and Jewish traditions in the Middle Ages, and it continues to influence Christian theology, especially Eastern Orthodox theology, and the scholastic tradition of the Roman Catholic Church. All aspects of Aristotle's philosophy continue to be the object of active academic study today.

Though Aristotle wrote many elegant treatises and dialogues (Cicero described his literary style as "a river of gold"), it is thought that the majority of his writings are now lost; it is believed that only about one third of the original works have survived.".

Life

Aristotle was born in Stagira, Chalcidice, in 384 BC. His father was the personal physician to King Amyntas of Macedon. Aristotle was trained and educated as a member of the aristocracy. At about the age of eighteen, he went to Athens to continue his education at Plato's Academy. Aristotle remained at the academy for nearly twenty years, not leaving until after Plato's death in 347 BC. He then traveled with Xenocrates to the court of Hermias of Atarneus in Asia Minor. While in Asia, Aristotle traveled with Theophrastus to the island of Lesbos, where together they researched the botany and zoology of the island. Aristotle married Hermias' daughter (or niece) Pythias. She bore him a daughter, whom they named Pythias. Soon after Hermias' death, Aristotle was invited by Philip of Macedon to become tutor to Alexander the Great and is said to have disciplined him by whippings.

After spending several years tutoring the young Alexander the Great, Aristotle returned to Athens. By 335 BC, he established his own school there, known as the Lyceum. Aristotle conducted courses at the school for the next twelve years. While in Athens, his wife Pythias died, and Aristotle became involved with Herpyllis of Stageira, who bore him a son whom he named after his father, Nicomachus. According to the Suda, he also had an eromenos, Palaephatus of Abydus.

It is during this period in Athens when Aristotle is believed to have composed many of his works. Aristotle wrote many dialogues, only fragments of which survived. The works that have survived are in treatise form and were not, for the most part, intended for widespread publication, as they are generally thought to be lecture aids for his students. His most important treatises include Physics, Metaphysics, Nicomachean Ethics, Politics, De Anima (On the Soul) and Poetics. These works, although connected in many fundamental ways, vary significantly in both style and substance.

Aristotle not only studied almost every subject possible at the time, but made significant contributions to most of them. In physical science, Aristotle studied anatomy, astronomy, economics, embryology, geography, geology, meteorology, physics and zoology. In philosophy, he wrote on aesthetics, ethics, government, metaphysics, politics, psychology, rhetoric and theology. He also studied education, foreign customs, literature and poetry. His combined works constitute a virtual encyclopedia of Greek knowledge. It has been suggested that Aristotle was probably the last person to know everything there was to be known in his own time. Upon Alexander's death, anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens once again flared. Eurymedon the hierophant denounced Aristotle for not holding the gods in honor. Aristotle fled the city to his mother's family estate in Chalcis, explaining, "I will not allow the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy," a reference to Athens's prior trial and execution of Socrates. However, he died in Euboea of natural causes within the year (in 322 BC). Aristotle left a will and named chief executor his student Antipater, in which he asked to be buried next to his wife.

Logic

Aristotle's conception of logic was the dominant form of logic until 19th century advances in mathematical logic. Kant stated in the Critique of Pure Reason that Aristotle's theory of logic completely accounted for the core of deductive inference.

History

Aristotle "says that 'on the subject of reasoning' he 'had nothing else on an earlier date to speak of'". However, Plato reports that syntax was devised before him, by Prodikos of Keos, who was concerned by the correct use of words. Logic seems to have emerged from dialectics; the earlier philosophers made frequent use of concepts like reductio ad absurdum in their discussions, but never truly understood the logical implications. Even Plato had difficulties with logic; although he had a reasonable conception of a deduction system, he could never actually construct one and relied instead on his dialectic, which confused science with methodology. Plato believed that deduction would simply follow from premises, hence he focused on maintaining solid premises so that the conclusion would logically follow. Consequently, Plato realized that a method for obtaining conclusions would be most beneficial. He never succeeded in devising such a method, but his best attempt was published in his book Sophist, where he introduced his division method.

Analytics and the Organon

What we today call Aristotelian logic, Aristotle himself would have labeled "analytics". The term "logic" he reserved to mean dialectics. Most of Aristotle's work is probably not in its original form, since it was most likely edited by students and later lecturers. The logical works of Aristotle were compiled into six books in about the early 1st century AD:

1 Categories

2 On Interpretation

3 Prior Analytics

4 Posterior Analytics

5 Topics

6 On Sophistical Refutations

The order of the books (or the teachings from which they are composed) is not certain, but this list was derived from analysis of Aristotle's writings. It goes from the basics, the analysis of simple terms in the Categories, to the study of more complex forms, namely, syllogisms (in the Analytics) and dialectics (in the Topics and Sophistical Refutations). There is one volume of Aristotle's concerning logic not found in the Organon, namely the fourth book of Metaphysics.

Modal logic

Aristotle is also the creator of syllogisms with modalities (modal logic). The word modal refers to the word 'modes', explaining the fact that modal logic deals with the modes of truth. Aristotle introduced the qualification of 'necessary' and 'possible' premises.

Aristotle's scientific method

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), a detail of The School of Athens, a fresco by Raphael. Aristotle gestures to the earth, representing his belief in knowledge through empirical observation and experience, while holding a copy of his Nicomachean Ethics in his hand, whilst Plato gestures to the heavens, representing his belief in The Forms.

Like his teacher Plato, Aristotle's philosophy aims at the universal. Aristotle, however, found the universal in particular things, which he called the essence of things, while Plato finds that the universal exists apart from particular things, and is related to them as their prototype or exemplar. For Aristotle, therefore, philosophic method implies the ascent from the study of particular phenomena to the knowledge of essences, while for Plato philosophic method means the descent from a knowledge of universal Forms (or ideas) to a contemplation of particular imitations of these. For Aristotle, "form" still refers to the unconditional basis of phenomena but is "instantiated" in a particular substance (see Universals and particulars, below). In a certain sense, Aristotle's method is both inductive and deductive, while Plato's is essentially deductive from a priori principles.

In Aristotle's terminology, "natural philosophy" is a branch of philosophy examining the phenomena of the natural world, and included fields that would be regarded today as physics, biology and other natural sciences. In modern times, the scope of philosophy has become limited to more generic or abstract inquiries, such as ethics and metaphysics, in which logic plays a major role. Today's philosophy tends to exclude empirical study of the natural world by means of the scientific method. In contrast, Aristotle's philosophical endeavors encompassed virtually all facets of intellectual inquiry.

In the larger sense of the word, Aristotle makes philosophy coextensive with reasoning, which he also would describe as "science". Note, however, that his use of the term science carries a different meaning than that covered by the term "scientific method". For Aristotle, "all science (dianoia) is either practical, poetical or theoretical" (Metaphysics 1025b25). By practical science, he means ethics and politics; by poetical science, he means the study of poetry and the other fine arts; by theoretical science, he means physics, mathematics and metaphysics.

If logic (or "analytics") is regarded as a study preliminary to philosophy, the divisions of Aristotelian philosophy would consist of: (1) Logic; (2) Theoretical Philosophy, including Metaphysics, Physics, Mathematics, (3) Practical Philosophy and (4) Poetical Philosophy.

In the period between his two stays in Athens, between his times at the Academy and the Lyceum, Aristotle conducted most of the scientific thinking and research for which he is renowned today. In fact, most of Aristotle's life was devoted to the study of the objects of natural science. Aristotle’s metaphysics contains observations on the nature of numbers but he made no original contributions to mathematics. He did, however, perform original research in the natural sciences, e.g., botany, zoology, physics, astronomy, chemistry, meteorology, and several other sciences.

Aristotle's writings on science are largely qualitative, as opposed to quantitative. Beginning in the sixteenth century, scientists began applying mathematics to the physical sciences, and Aristotle's work in this area was deemed hopelessly inadequate. His failings were largely due to the absence of concepts like mass, velocity, force and temperature. He had a conception of speed and temperature, but no quantitative understanding of them, which was partly due to the absence of basic experimental devices, like clocks and thermometers.

His writings provide an account of many scientific observations, a mixture of precocious accuracy and curious errors. For example, in his History of Animals he claimed that human males have more teeth than females. In a similar vein, John Philoponus, and later Galileo, showed by simple experiments that Aristotle's theory that the more massive object falls faster than a less massive object is incorrect. On the other hand, Aristotle refuted Democritus's claim that the Milky Way was made up of "those stars which are shaded by the earth from the sun's rays," pointing out (correctly, even if such reasoning was bound to be dismissed for a long time) that, given "current astronomical demonstrations" that "the size of the sun is greater than that of the earth and the distance of the stars from the earth many times greater than that of the sun, then...the sun shines on all the stars and the earth screens none of them."

In places, Aristotle goes too far in deriving 'laws of the universe' from simple observation and over-stretched reason. Today's scientific method assumes that such thinking without sufficient facts is ineffective, and that discerning the validity of one's hypothesis requires far more rigorous experimentation than that which Aristotle used to support his laws.

Aristotle also had some scientific blind spots, the largest being his inability to see the application of mathematics to physics. Aristotle held that physics was about changing objects with a reality of their own, whereas mathematics was about unchanging objects without a reality of their own. In this philosophy, he could not imagine that there was a relationship between them. He also posited a flawed cosmology that we may discern in selections of the Metaphysics, which was widely accepted up until the 1500s. From the 3rd century to the 1500s, the dominant view held that the Earth was the center of the universe (geocentrism).

Since he was perhaps the philosopher most respected by European thinkers during and after the Renaissance, these thinkers often took Aristotle's erroneous positions as given, which held back science in this epoch. However, Aristotle's scientific shortcomings should not mislead one into forgetting his great advances in the many scientific fields. For instance, he founded logic as a formal science and created foundations to biology that were not superseded (in the West) for two millennia. Moreover, he introduced the fundamental notion that nature is composed of things that change and that studying such changes can provide useful knowledge of underlying constants. This made the study of physics, and all other sciences, respectable. In actuality, however, this observation transcends physics into metaphysics.

Physics

The five elements

Fire, which is hot and dry.

Earth, which is cold and dry.

Air, which is hot and wet.

Water, which is cold and wet.

Aether, which is the divine substance that makes up the heavenly spheres and

heavenly bodies (stars and planets).

Each of the four earthly elements has its natural place; the earth at the centre of the universe, then water, then air, then fire. When they are out of their natural place they have natural motion, requiring no external cause, which is towards that place; so bodies sink in water, air bubbles up, rain falls, flame rises in air. The heavenly element has perpetual circular motion.

Causality - The Four Causes

The material cause is that from which a thing comes into existence as from its parts, constituents, substratum or materials. This reduces the explanation of causes to the parts (factors, elements, constituents, ingredients) forming the whole (system, structure, compound, complex, composite, or combination), a relationship known as the part-whole causation.

The formal cause tells us what a thing is, that any thing is determined by the definition, form, pattern, essence, whole, synthesis or archetype. It embraces the account of causes in terms of fundamental principles or general laws, as the whole (i.e., macrostructure) is the cause of its parts, a relationship known as the whole-part causation.

The efficient cause is that from which the change or the ending of the change

first starts. It identifies 'what makes of what is made and what causes change

of what is changed' and so suggests all sorts of agents, nonliving or living,

acting as the sources of change or movement or rest. Representing the current

understanding of causality as the relation of cause and effect, this covers

the modern definitions of "cause" as either the agent or agency or

particular events or states of affairs.

The final cause is that for the sake of which a thing exists or is done,

including both purposeful and instrumental actions and activities. The final

cause or telos is the purpose or end that something is supposed to serve, or

it is that from which and that to which the change is. This also covers modern

ideas of mental causation involving such psychological causes as volition,

need, motivation, or motives, rational, irrational, ethical, all that gives

purpose to behavior.

Additionally, things can be causes of one another, causing each other reciprocally, as hard work causes fitness and vice versa, although not in the same way or function, the one is as the beginning of change, the other as the goal. (Thus Aristotle first suggested a reciprocal or circular causality as a relation of mutual dependence or influence of cause upon effect). Moreover, Aristotle indicated that the same thing can be the cause of contrary effects; its presence and absence may result in different outcomes.

Aristotle marked two modes of causation: proper (prior) causation and accidental (chance) causation. All causes, proper and incidental, can be spoken as potential or as actual, particular or generic. The same language refers to the effects of causes, so that generic effects assigned to generic causes, particular effects to particular causes, operating causes to actual effects. Essentially, causality does not suggest a temporal relation between the cause and the effect.

All further investigations of causality will consist of imposing the favorite hierarchies on the order causes, such as final > efficient > material > formal (Thomas Aquinas), or of restricting all causality to the material and efficient causes or to the efficient causality (deterministic or chance) or just to regular sequences and correlations of natural phenomena (the natural sciences describing how things happen instead of explaining the whys and wherefores).

Chance and spontaneity

Spontaneity and chance are causes of effects. Chance as an incidental cause lies in the realm of accidental things. It is "from what is spontaneous" (but note that what is spontaneous does not come from chance). For a better understanding of Aristotle's conception of "chance" it might be better to think of "coincidence": Something takes place by chance if a person sets out with the intent of having one thing take place, but with the result of another thing (not intended) taking place. For example: A person seeks donations. That person may find another person willing to donate a substantial sum. However, if the person seeking the donations met the person donating, not for the purpose of collecting donations, but for some other purpose, Aristotle would call the collecting of the donation by that particular donator a result of chance. It must be unusual that something happens by chance. In other words, if something happens all or most of the time, we cannot say that it is by chance.

There is also more specific kind of chance, which Aristotle names "luck", that can only apply to human beings, since it is in the sphere of moral actions. According to Aristotle, luck must involve choice (and thus deliberation), and only humans are capable of deliberation and choice. "What is not capable of action cannot do anything by chance".

Metaphysics

Aristotle defines metaphysics as "the knowledge of immaterial being," or of "being in the highest degree of abstraction." He refers to metaphysics as "first philosophy", as well as "the theologic science."

Substance, potentiality and actuality

Aristotle examines the concept of substance (ousia) in his Metaphysics, Book VII and he concludes that a particular substance is a combination of both matter and form. As he proceeds to the book VIII, he concludes that the matter of the substance is the substratum or the stuff of which it is composed, e.g. the matter of the house are the bricks, stones, timbers etc., or whatever constitutes the potential house. While the form of the substance, is the actual house, namely ‘covering for bodies and chattels’ or any other differentia (see also predicables). The formula that gives the components is the account of the matter, and the formula that gives the differentia is the account of the form.

With regard to the change (kinesis) and its causes now, as he defines in his Physics and On Generation and Corruption 319b-320a, he distinguishes the coming to be from 1. growth and diminution, which is change in quantity 2. locomotion, which is change in space and 3. alteration, which is change in quality. The coming to be is a change where nothing persists of which the resultant is a property. In that particular change he introduces the concept of potentiality (dynamis) and actuality (entelecheia) in association with the matter and the form.

Referring to potentiality, this is what a thing is capable of doing, or being acted upon, if it is not prevented by something else. For example, the seed of a plant in the soil is potentially (dynamei) plant, and if is not prevented by something, it will become a plant. Potentially beings can either 'act' (poiein) or 'be acted upon' (paschein), which can be either innate or learned. For example, the eyes possess the potentiality of sight (innate - being acted upon), while the capability of playing the flute can be possessed by learning (exercise - acting).

Actuality is the fulfilment of the end of the potentiality. Because the end (telos) is the principle of every change, and for the sake of the end exists potentiality, therefore actuality is the end. Referring then to our previous example, we could say that actuality is when the seed of the plant becomes a plant.

“ For that for the sake of which a thing is, is its principle, and the becoming is for the sake of the end; and the actuality is the end, and it is for the sake of this that the potentiality is acquired. For animals do not see in order that they may have sight, but they have sight that they may see.”

In conclusion, the matter of the house is its potentiality and the form is its actuality. The formal cause (aitia) then of that change from potential to actual house, is the reason (logos) of the house builder and the final cause is the end, namely the house itself. Then Aristotle proceeds and concludes that the actuality is prior to potentiality in formula, in time and in substantiality.

With this definition of the particular substance (i.e., matter and form), Aristotle tries to solve the problem of the unity of the beings, e.g., what is that makes the man one? Since, according to Plato there are two Ideas: animal and biped, how then is man a unity? However, according to Aristotle, the potential being (matter) and the actual one (form) are one and the same thing.

Universals and particulars

Aristotle's predecessor, Plato, argued that all things have a universal form, which could be either a property, or a relation to other things. When we look at an apple, for example, we see an apple, and we can also analyze a form of an apple. In this distinction, there is a particular apple and a universal form of an apple. Moreover, we can place an apple next to a book, so that we can speak of both the book and apple as being next to each other.

Plato argued that there are some universal forms that are not a part of particular things. For example, it is possible that there is no particular good in existence, but "good" is still a proper universal form. Bertrand Russell is a contemporary philosopher that agreed with Plato on the existence of "uninstantiated universals".

Aristotle disagreed with Plato on this point, arguing that all universals are "instantiated". Aristotle argued that there are no universals that are unattached to existing things. According to Aristotle, if a universal exists, either as a particular or a relation, then there must have been, must be currently, or must be in the future, something on which the universal can be predicated. Consequently, according to Aristotle, if it is not the case that some universal can be predicated to an object that exists at some period of time, then it does not exist. One way for contemporary philosophers to justify this position is by asserting the eleatic principle.

In addition, Aristotle disagreed with Plato about the location of universals. As Plato spoke of the world of the forms, a location where all universal forms subsist, Aristotle maintained that universals exist within each thing on which each universal is predicated. So, according to Aristotle, the form of apple exists within each apple, rather than in the world of the forms.

Biology and medicine

Empirical research program

Aristotle is the earliest natural historian whose work has survived in some detail. Aristotle did his research on natural history on the isle of Lesbos. The works that reflect this research, including History of Animals, Generation of Animals, and Parts of Animals, contain some remarkable observations and interpretations, along with sundry myths and mistakes. The most striking passages are about the sea-life visible from observation on Lesbos and available from the catches of fishermen. His observations on catfish, electric fish (Torpedo) and angler-fish are exceptional, as is his writing on cephalopods, molluscs, octopus, sepia (cuttlefish) and the paper nautilus (Argonauta argo). His description of the hectocotyl arm (see cephalopod) was about two thousand years ahead of its time, and widely disbelieved until its rediscovery in the nineteenth century. He separated the aquatic mammals from fish, and knew that sharks and rays were part of the group he called Selache (selachians). He gave accurate descriptions of ruminants' four-chambered fore-stomachs, and of the unusual mammal-like embryological development of the hound shark Mustelus laevis.

Theory of biological being

However, for Charles Singer, "Nothing is more remarkable than [Aristotle's] efforts to [exhibit] the relationships of living things as a scala naturae" Aristotle's History of Animals classified organisms in relation to a hierarchical "Ladder of Life" (scala naturae), placing them according to complexity of structure and function so that higher organisms showed greater vitality and ability to move.

Aristotle believed that intellectual purposes, i.e., formal causes, guided all natural processes. Such a teleological view gave Aristotle cause to justify his observed data as an expression of formal design. Noting that "no animal has, at the same time, both tusks and horns," and "a single-hooved animal with two horns I have never seen," Aristotle suggested that Nature, giving no animal both horns and tusks, was staving off vanity, and giving creatures faculties only to such a degree as they are necessary. Noting that ruminants had a multiple stomachs and weak teeth, he supposed the first was to compensate for the latter, with Nature trying to preserve a type of balance.

In a similar fashion, Aristotle believed that creatures were arranged in a graded scale of perfection rising from plants on up to man, the scala naturae or Great Chain of Being. His system had eleven grades, arranged according "to the degree to which they are infected with potentiality", expressed in their form at birth. The highest animals laid warm and wet creatures alive, the lowest bore theirs cold, dry, and in thick eggs.

Aristotle also held that the level of a creature's perfection was reflected in its form, but not foreordained by that form. He placed great importance on the type(s) of soul an organism possessed, asserting that plants possess a vegetative soul, responsible for reproduction and growth, animals a vegetative and a sensitive soul, responsible for mobility and sensation, and humans a vegetative, a sensitive, and a rational soul, capable of thought and reflection.

Aristotle, in contrast to earlier philosophers, but in accordance with the Egyptians, placed the rational soul in the heart, rather than the brain. Notable is Aristotle's division of sensation and thought, which generally went against previous philosophers, with the exception of Alcmaeon.

His analysis of procreation is frequently criticized on the grounds that it presupposes an active, ensouling masculine element bringing life to an inert, passive, lumpen female element; it is on these grounds that Aristotle is considered by some feminist critics to have been a misogynist.

Aristotle's successor - Theophrastus

Aristotle's successor at the Lyceum, Theophrastus, wrote a series of books on botany — the History of Plants — which survived as the most important contribution of antiquity to botany, even into the Middle Ages. Many of Theophrastus' names survive into modern times, such as carpos for fruit, and pericarpion for seed vessel.

Rather than focus on formal causes, as Aristotle did, Theophrastus suggested a mechanistic scheme, drawing analogies between natural and artificial processes, and relying on Aristotle's concept of the efficient cause. Theophrastus also recognized the role of sex in the reproduction of some higher plants, though this last discovery was lost in later ages.

The effect of Aristotle on Hellenistic medicine

Following Theophrastus, the Lyceum failed to produce any original work. Though interest in Aristotle's ideas survived, they were generally taken unquestioningly. It is not until the age of Alexandria under the Ptolemies that advances in biology can be again found.

The first medical teacher at Alexandria Herophilus of Chalcedon, corrected Aristotle, placing intelligence in the brain, and connected the nervous system to motion and sensation. Herophilus also distinguished between veins and arteries, noting that the latter pulse while the former do not. Though a few ancient atomists such as Lucretius challenged the teleological viewpoint of Aristotelian ideas about life, teleology (and after the rise of Christianity, natural theology) would remain central to biological thought essentially until the 18th and 19th centuries. In the words of Ernst Mayr, "Nothing of any real consequence in biology after Lucretius and Galen until the Renaissance." (in Europe at least - advancement in the field continued in the Middle East and orient). Aristotle's ideas of natural history and medicine survived, but they were generally taken unquestioningly.

Practical Philosophy

Ethics

Aristotle considered ethics to be a practical science, i.e., one mastered by doing rather than merely reasoning. Further, Aristotle believed that ethical knowledge is not certain knowledge (like metaphysics and epistemology) but is general knowledge. He wrote several treatises on ethics, including most notably, Nichomachean Ethics, in which he outlines what is commonly called virtue ethics.

Aristotle taught that virtue has to do with the proper function of a thing. An eye is only a good eye in so much as it can see, because the proper function of an eye is sight. Aristotle reasoned that man must have a function uncommon to anything else, and that this function must be an activity of the soul. Aristotle identified the best activity of the soul as eudaimonia: a happiness or joy that pervades the good life. Aristotle taught that to achieve the good life, one must live a balanced life and avoid excess. This balance, he taught, varies among different persons and situations, and exists as a golden mean between two vices - one an excess and one a deficiency.

Politics

In addition to his works on ethics, which address the individual, Aristotle addressed the city in his work titled Politics. Aristotle's conception of the city is very organic, and he is considered one of the first to conceive of the city in this manner. Aristotle considered the city to be a natural community. Moreover, he considered the city to be prior to the family which in turn is prior to the individual, i.e., last in the order of becoming, but first in the order of being (1253a19-24). He is also famous for his statement that "man is by nature a political animal." Aristotle conceived of politics as being rather like an organism than like a machine, and as a collection of parts that cannot exist without the other.

It should be noted that the modern understanding of a political community is that of the state. However, the state was foreign to Aristotle. He referred to political communities as cities. Aristotle understood a city as a political "partnership" (1252a1) and not one of a social contract (or compact) or a political community as understood by Niccolò Machiavelli. Subsequently, a city is created not to avoid injustice or for economic stability (1280b29-31), but rather to live a good life: "The political partnership must be regarded, therefore, as being for the sake of noble actions, not for the sake of living together" (1281a1-3). This can be distinguished from the social contract theory which individuals leave the state of nature because of "fear of violent death" or its "inconveniences."

Rhetoric and poetics

Aristotle considered epic poetry, tragedy, comedy, dithyrambic poetry and music to be imitative, each varying in imitation by media, object, and manner. For example, music imitates with the media of rhythm and harmony, whereas dance imitates with rhythm alone, and poetry with language. The forms also differ in their object of imitation. Comedy, for instance, is a dramatic imitation of men worse than average; whereas tragedy imitates men slightly better than average. Lastly, the forms differ in their manner of imitiation - through narrative or character, through change or no change, and through drama or no drama. Aristotle believed that imitiation is natural to mankind and constitutes one of mankind's advantages over animals.

While it is believed that Aristotle's Poetics was comprised of two books - one on comedy and one on tragedy - only the portion that focuses on tragedy has survived. Aristotle taught that tragedy is composed of six elements: plot-structure, character, style, spectacle, and lyric poetry. The characters in a tragedy are merely a means of driving the story; and the plot, not the characters, is the chief focus of tragedy. Tragedy is the imitation of action arousing pity and fear, and is meant to effect the catharsis of those same emotions. Aristotle concludes Poetics with a discussion on which, if either, is superior: epic or tragic mimesis. He suggest that because tragedy possesses all the attributes of an epic, possibly possesses additional attributes such as spectacle and music, is more unified, and achieves the aim of its mimesis in shorter scope, it can be considered superior to epic.

The loss of his works

According to a distinction that originates with Aristotle himself, his writings are divisible into two groups: the "exoteric" and the "esoteric". Most scholars have understood this as a distinction between works Aristotle intended for the public (exoteric), and the more technical works (esoteric) intended for the narrower audience of Aristotle's students and other philosophers who were familiar with the jargon and issues typical of the Platonic and Aristotelian schools. Another common assumption is that none of the exoteric works is extant - that all of Aristotle's extant writings are of the esoteric kind. Current knowledge of what exactly the exoteric writings were like is scant and dubious, though many of them may have been in dialogue form. (Fragments of some of Aristotle's dialogues have survived.) Perhaps it is to these that Cicero refers when he characterized Aristotle's writing style as "a river of gold"; it is hard for many modern readers to accept that one could seriously so admire the style of those works currently available to us. However, some modern scholars have warned that we cannot know for certain that Cicero's praise was reserved specifically for the exoteric works; a few modern scholars have actually admired the concise writing style found in Aristotle's extant works.

One major question in the history of Aristotle's works, then, is how were the exoteric writings all lost, and how did the ones we now possess come to us? The story of the original manuscripts of the esoteric treatises is described by Strabo in his Geography and Plutarch in his Parallel Lives. The manuscripts were left from Aristotle to his successor Theophrastus, who in turn willed them to Neleus of Scepsis. Neleus supposedly took the writings from Athens to Scepsis, where his heirs let them languish in a cellar until the first century BC, when Apellicon of Teos discovered and purchased the manuscripts, bringing them back to Athens. According to the story, Apellicon tried to repair some of the damage that was done during the manuscripts' stay in the basement, introducing a number of errors into the text. When Lucius Cornelius Sulla occupied Athens in 86 BC, he carried off the library of Apellicon to Rome, where they were first published in 60 BC by the grammarian Tyrranion of Amisus and then by philosopher Andronicus of Rhodes.

Carnes Lord attributes the popular belief in this story to the fact that it provides "the most plausible explanation for the rapid eclipse of the Peripatetic school after the middle of the third century, and for the absence of widespread knowledge of the specialized treatises of Aristotle throughout the Hellenistic period, as well as for the sudden reappearance of a flourishing Aristotelianism during the first century B.C." Lord voices a number of reservations concerning this story, however. First, the condition of the texts is far too good for them to have suffered considerable damage followed by Apellicon's inexpert attempt at repair. Second, there is "incontrovertible evidence," Lord says, that the treatises were in circulation during the time in which Strabo and Plutarch suggest they were confined within the cellar in Scepsis. Third, the definitive edition of Aristotle's texts seems to have been made in Athens some fifty years before Andronicus supposedly compiled his. And fourth, ancient library catalogues predating Andronicus' intervention list an Aristotelean corpus quite similar to the one we currently possess. Lord sees a number of post-Aristotelean interpolations in the Politics, for example, but is generally confident that the work has come down to us relatively intact.

After the Roman period, Aristotle's works were by and large lost to the West for a second time. They were, however, preserved in the East by various Muslim scholars and philosophers, many of whom wrote extensive commentaries on his works. Aristotle lay at the foundation of the falsafa movement in Islamic philosophy, stimulating the thought of Al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, Ibn Rushd and others.

As the influence of the falsafa grew in the West, in part due to Gerard of Cremona's translations and the spread of Averroism, the demand for Aristotle's works grew. William of Moerbeke translated a number of them into Latin. When Thomas Aquinas wrote his theology, working from Moerbeke's translations, the demand for Aristotle's writings grew and the Greek manuscripts returned to the West, stimulating a revival of Aristotelianism in Europe, and ultimately revitalizing European thought through Muslim influence in Spain to fan the embers of the Renaissance.

Legacy

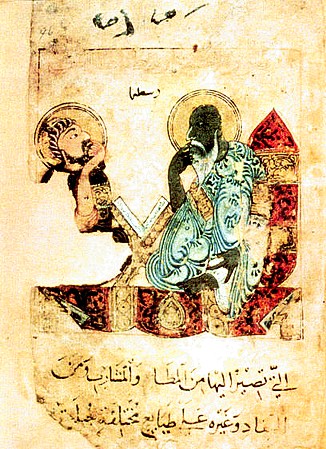

Early Islamic portrayal of Aristotle